Have you ever felt that sense where God, your conscience, or your gut was pushing you to do something you did not want to do? Where nothing in your rational mind thought it to be a good idea, but everything in your subconscious was crushing against your soul with restless pressure? Well, that is what this story is all about. In fear, it’s one I would prefer not to write, yet I know fear is the opposite of what it means to walk in God’s perfect love. As Bonhoeffer reminds, the issue always at stake is not “How can I be good?” nor “How can I do good?” but rather “What is the will of God?” For me, this act is God’s will.

Yet I admit, my fears regarding the subject are anything but the product of paranoid speculation. The current climate of our divided society reminds me daily that what I’m about to embark upon risks the wrath of the culture war gods. Yes, the never slumbering metaverse is always willing to pour out indignation unto exile. Yet, it is my observation that contrary to how this pejorative is wielded, the “woke cancel culture” is as much a feature of the conservative religious right as it is of the liberal irreligious left. It might better be described as “anti-woke cancel culture,” but it’s merely the flip of the same coin. In fact, it was my own evangelical heritage that inaugurated what some progressives have gone on to perfect. Both are all too willing to leverage fear, shame, force, outrage, financial punishment, and social banishment as tools of compliance. Neither of which reminds me of the upside-down and backward ethos of Jesus. Of the latter group, I have no such expectations; thus, I take no offense. Of the former, it breaks my heart and often tests my own resolve for reasons that will become apparent.

Thus I write – a rather long story – as an evangelical.

To my fellow evangelicals (though everyone is free to come along).

About painful failures and lessons learned as the parent of an LGBT+ child.

And so… (deep breath)… let’s begin.

Last month was June.

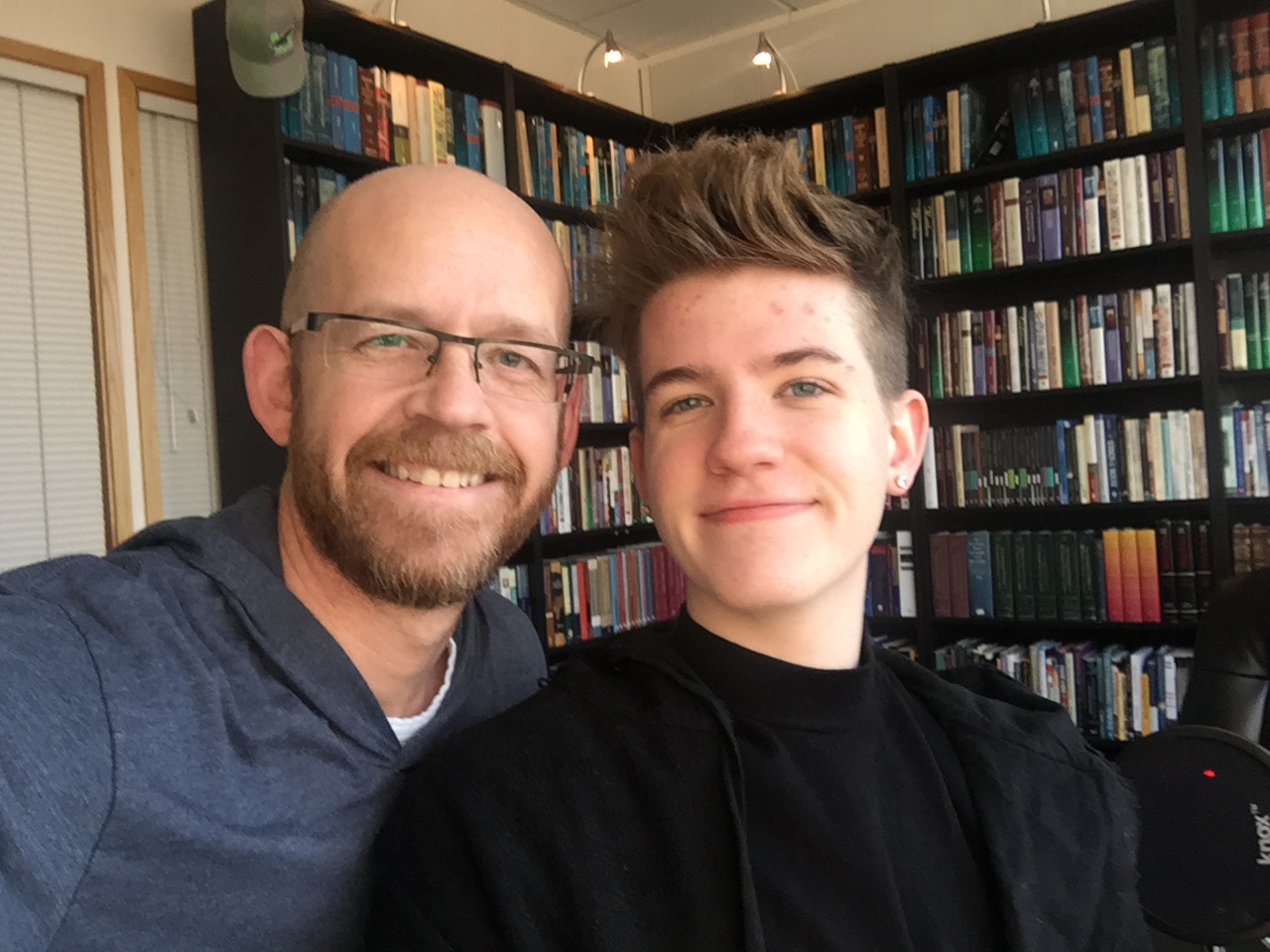

In the Boswell home, June is the busiest month of the year. My wife’s birthday is on the 4th. Our anniversary immediately comes on the 9th. Followed by our oldest daughter’s birthday on the 11th. And then, finally, at the end of the month is the birthday of our youngest and only son Grayson. Gray is our baby (though he’s rolling in on 23 years old and stands taller than his old man now). He was always a happy kid. Right there in the moment. Never focusing too much on what was behind, nor worrying about what was up ahead. A kid who would take 30 minutes to fulfill a 5-minute task as he got sucked into a hundred tiny distractions along the way. In many ways, Gray was the life of the home.

At 12 years old Gray’s world changed. Our world changed. I’m uncertain exactly when Gray knew the earth was shifting under his feet. We’ve never really discussed that element, but at 12, his inner world spilled into our world as a family. One day I came upon Gray playing a video game where his avatar presented with some possibly gay markers. He quickly tried to turn off the game so I didn’t see, but he was just a bit too slow on the draw. Instantly he jumped onto his bed and buried his face in his pillow. He reacted as one caught, exposed, afraid. My wife and I sat with him on his bed, trying to coax him out like a wounded pup under a chair. Finally, I spoke the words I was as afraid to ask. Words he was terrified to answer, “Grayson, do you think you’re gay?” It’s a moment that I will never forget. He turned his face to us, looking as helpless as any human could, and immediately buried his face back into his pillow, crying. The answer spoken without a word. That day the world tilted for us all. A gay kid, from a pastor’s family, in an evangelical environment. How would that play? I wish I could say I handled it with grace and wisdom.

I did not.

Why did I not?

I recall my first exposure to anything about homosexuality was in elementary school. At recess, we would all rush from the classroom to our janky red dirt and gravel playground. It was there the recess game of the day would collectively choose us. While there was a rotating menagerie of favorites, two were the most prevalent. The first was Kickball, where the object was less a foot-based version of baseball and more about trying to kick the ball so hard your slip-on Vans flew off on impact with the ball and cleared 2nd base (moment of confession, we would all front load the kick by pulling our heel out of the shoe to ensure a solid flight time for those sweet checkered kicks). The second game was more straightforward, Smear the Queer (and yes, that feels uncomfortable to write). Here someone was branded “the queer,” and everyone else chased the queer until you caught them and then threw, flung, or forced them to the ground. Hence, you smeared the queer. But hey, it was the mid-1970s, and gays weren’t well-liked.

Around this time, our school had a new student. Being a small town, outsiders were always a curiosity to our ingrown ecosystem, and Adrian was as outsider as you can get. He talked differently, dressed oddly in short coveralls, and came from a place called Austria. When we would all go to the boy’s bathroom after recess, Adrian would unbuckle his coveralls, drop them to the floor, and pee at the urinal with his gleaming Austrian butt for all to see. “You know why he does that?” Sam asked me, “It’s because he’s a fa__ot.” By 4th grade, I was aware enough to know what Sam was saying. None of us had a clue if Adrian was gay or not. But the label stuck, and Adrian was mercilessly picked on as long as I knew him. In fact, the first time I ever saw a person punched in the face and knocked completely unconscious was Adrian. We were playing Smear the Queer, Adrian was just about to reach the “queer,” when the kid turned around and dropped Adrian cold. His reason, “I’m not letting some fa__ot touch me.” But hey, it was the late 1970s, and gays weren’t well-liked.

In high school, I knew of a couple of kids that might be gay, along with one of the girl’s P.E. teachers everyone assumed to be a lesbian. But everyone stayed firmly tucked away in closets. Base words such as d_ke, queer, fa_, fa__ot, and homo were spoken into the air with impunity. There was no sense of a future “wokeness” that would one day displace these as staples in public discourse. People would joke around about the limp-wristed types who spoke with a lisp and had a high fashion sense. Often there were creative innuendos that would make Eddie Murphy’s stand-up special “Raw” feel like a PG-13 TED Talk. Needless to say, to be gay was to be a social pariah. Queers were for smearing, mocking, and generally laughing at. But hey, it was the mid-1980’s and gays weren’t well-liked.

As high school was nearing a close, I enlisted in the Navy through the delayed entry program. One of the steps in this process is MEPS, the Military Entrance Processing Station. Here you are tested for aptitude, physical fitness, and other criteria. The two most common questions I encountered throughout the process were (a) “Have you done drugs?” and (b) “Are you gay?” Not, “Have you ever considered selling secrets to the Soviets?” or “Have you rooted for Army instead of Navy in the college matchup?” Nope, I was asked twice about drugs and perhaps five to six times if I was gay. In fact, at one point, I was with some other kid who was hoping to be Army bound. As we were going through a physical, the doctor sprung both questions on the two of us. I gave a snappy “No sir.” to both questions. My MEPS partner, on the other hand, was “No” to being gay but “Yes” to drugs, weed particularly. “How many times have you smoked weed?” the doctor asked. “Uh, probably between 700-800 times.” The previous night being the most recent occasion. The next time I saw this kid, he was swearing into the United States Army. Had he said “Yes” to the gay question, he would have been disqualified on the spot. But hey, it was the late 1980s, and gays weren’t well-liked.

A few years later, I was in a pastoral internship and taking classes at a local community college. For an elective course, I decided to take a class I figured would be an easy 5-credits, “Intercultural Communications.” I was a decent communicator and thought the class would be about giving speeches on various cultural assignments. Nope, not at all. It was about learning from and communicating with people from various sub-cultures. It was here I heard my first insider baseball talk from the gay community. Up to this point, I was only exposed to one side, the side of my childhood. From there, I graduated into the voices of “The Religious Right” and the “Moral Majority,” which were engaged in a culture war for the soul of America. I was an evangelical, and all evangelicals were well versed in the dangers of “The Gay Agenda” that was seeking to push “special rights” above everyone else’s good old fashion Constitutional rights. The question of gays in the military was on the table with “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” and the rhetoric was at a fever pitch. But, in this class, on some average Tuesday, I was exposed to a side of the discussion I had never experienced before. Real people discussing their real challenges, traumas, and heartbreak. I can’t recall either of the men’s names, but I vividly remember the emotion of that room and the profound shift in my heart toward this community. Both had been beaten up for being gay. Their families had rejected both. One was just diagnosed with AIDS, and the other was worried for his non-partner friend. My evangelical spaces had all sorts of theories for why these men “chose to be gay,” as it was framed. Their moms were too controlling. Their dads were uninvolved. Both were most certainly molested, of course. They also had theories on why the one man was doomed to die of AIDS, God’s judgment on his immoral behavior. AIDS was God’s solution to the gay epidemic. Countless women and children were also inflicted with AIDS throughout Africa due to infidelity and rape. However, they were people of color and way over there, the unfortunate collateral damage of God’s war on queers. That was the standard evangelical attitude in those days. But hey, it was the early to mid-1990s, and gays weren’t well-liked.

Shortly after this small step into the gay world, I had my first true set of gay friends, but I didn’t know they were gay. They were deep in the back of the closet behind grandpas old raincoat. One was Jon, the pastoral intern whom I eventually replaced. Jon and I met together weekly for well over a year. He was an awesome guy. Thoughtful, funny, and intelligent. He had a long-time girlfriend whom he had never kissed. I thought that strange at the time. This was before the whole “I Kissed Dating Goodbye, So Don’t Kiss A Girl Till You’re Married, Or You’re Not Serious About Your God” craze, so having never kissed her after years of being together should have been some sign. Anyway, Jon and I had a lot of transparent conversations where, in retrospect, I think he was trying to come out, but the risk of loss was just too high. Eventually, Jon did come out, a few years after we lost contact, and with that, he lost both his church friends and his Catholic family. Another friend was Greg. Greg was a student in our youth program, where I interned and eventually pastored. Greg was the mega servant guy. He was always showing up early, always staying late. Greg was the person you could depend on. I assumed when he graduated from high school, he might pivot into our internship program to become a pastor one day. Instead, Greg enlisted into the Marine Corps, and man, talk about a transformation. Greg was a husky guy going in, but came out of boot camp 100% a Bulldog. He lived, breathed, loved, and was willing to die a Jarhead for country and kin. And it was as a Marine that Greg began to explore the deep secret of his homosexuality. The era of no gays in the military hit the infamous slippery slope in the 90s when it acknowledged there were, in fact, gays in the military. To combat the problem, a president loathsome to evangelicals named Bill Clinton pushed for the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy. Evangelical leaders warned the move to be the end of the U.S. military and American greatness, but so far, everything is still standing. For a while, Greg sought to comply, but the pressure mounted. Unable to reconcile the Marine Corps values of Honor, Courage, Commitment, Integrity, his deeply held Christian faith, and his secret homosexuality, Greg sought to take his own life. The attempt landed him in a military hospital and under the eye of his command. For weeks they grilled him daily on why he attempted to kill himself. Greg would soon discover that “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” cuts one direction, the higher-ups can put a lot of pressure on the asking, and your job as a lowly grunt is to hold up and not tell. Greg finally told and was instantly greeted with Uncle Sam’s boot. A few days later, I found Greg on my doorstep in a daze. Unceremoniously ejected from everything that had been his identity and on the heels of a suicide attempt. In this fragile state, recovering from the trauma and figuring out what’s next with his life, the church we both had formerly attended publicly excommunicated Greg during three Sunday services for his homosexuality. In some recent messaging back and forth, Greg shared how outside of myself, “Pretty much damn near everyone pushed me away at that point.” More than 13,500 service members were dismissed under the 1993 law. But hey, it was the mid to late 1990s, and gays weren’t well-liked.

In 2000 my son was born.

Gays still weren’t well-liked.

Twelve years down the road, we would discover our son is gay.

Would he be liked?

The span of the “aughts” (2000-2009) did see a shift in public tone. The culture wars sided up more evenly as stronger voices for gay rights and equity emerged to enter the arena against the moral majority. But the general tomes remained from the conservative religious community; gays clearly weren’t well-liked by evangelicals.

In 2001 Jerry Falwell suggested that the terrorist attacks of 9/11 were God’s judgment on America for, among other things, the gays. On the Pat Roberson’s 700 Club program, Falwell emphatically proclaimed, “I point the finger in their face and say ‘you helped this happen.'” “Well, I totally concur,” responded Robertson. But hey, it was 2001, eleven years from finding out my son was gay. Clearly, gays weren’t well-liked by evangelicals.

During this period, there was the recurrent parade of boycotts, protests, and petitions to fight off “The Gay Agenda.” McDonald’s and Disney decided to allow employees to add “partners” to the health insurance plans. So a trifecta of the Southern Baptists, the American Family Association, and Focus on the Family called for an 8-yearlong boycott. Micky and McNuggets were out. We needed to use the power of Caesar’s money to force Christian morality on culture at large (and yes, that should sound ridiculous based on what Jesus says about money). I never understood why we didn’t want people to have health care, but it was a thing. Phrases such as “Hollywood is just shoving all this gay stuff down our throats.” was in vogue in my circles. I remember joking with my wife once that shows may need to give a trigger warning for conservative religious people, “Yes, this show will have a ‘token’ gay person or couple; watch at your own risk.” Clearly, gays weren’t well-liked by evangelicals.

Toward the end of the “aughts” the liberal land of California introduced Proposition 8, which passed with a 52% yes vote. What was Proposition 8? It declared that marriage was only between a man and a woman. Yes, in the land of Hollywood, hippies, and the homeland of the Pride movement, as recently as 2008, it was decided that homosexual marriage was still off-limits, even in California. Evangelicals saw this as validation that even those godless Californians were willing to hold the moral line. But hey, it was 2008, four years from finding out my son was gay. Clearly, gays weren’t well-liked by evangelicals.

In 2010 the Clinton-era legislation of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was on the repeal stack before the U.S. Senate. Initially, Republicans managed to block the legislation with a 57-40 vote. When revisited, a GOP-led filibuster was attempted, but a supermajority procedural vote moved the bill past the threat of a Republican filibuster. During this time, military chaplains were most opposed to the change in legislation. Their concern was that they would be required to treat LGBT+ soldiers, airmen, and sailors the same as their heterosexual counterparts openly. Evangelical leaders also raised several objections, not only about the possibility of restricted religious freedoms for military chaplains but warned how the very survival of the republic was at stake if homosexuals openly served. They predicted a gutted military that would face catastrophic consequences for our nation in a time of war. Much of this idea was based on the notion that military success as a nation is directly tied to our collective holiness as a nation before God – our “blessability.” Just as in the Old Testament, where obedience and disobedience was the decisive issue in military victory, so too evangelicals sought to impose this on the American fighting force as a type of biblically rooted superiority. In the end, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was repealed. Most Americans favored it in the spirit of Barry Goldwater, who said, “You don’t have to be straight to shoot straight.” Most evangelicals, however, vilified it as yet another slouch toward Sodom and Gomorrah. But hey, it was 2010, two years from finding out my son was gay. Clearly, gays weren’t well-liked by evangelicals.

So, way back in 2002, shortly after “the gays were partly to blame for the 9/11 terrorist attacks,” the Southern Poverty Law Center began a program called “Mix It Up at Lunch Day.” The purpose was “to encourage students to cross social boundaries, disregard stereotypes, and shut down cliques by sitting with someone new at lunch.” The campaign operated in tandem with broader anti-bullying initiatives across the country and had grown from just a handful of schools in 2002 to over 2500 within ten years. However, in 2012 the program came under fire from the American Family Association as being “a nationwide push to promote the homosexual lifestyle in public schools.” Mind you that nowhere in any of the materials were gay or lesbian issues specifically addressed, but the AFA maintained that “Anti-bullying legislation is… just another thinly veiled attempt to promote the homosexual agenda.” Based on this conjecture, parents were encouraged to keep their kids home from “Mix It Up at Lunch Day.” But hey, it was 2012. And I had just found out my son was gay. And clearly, still, gays weren’t well-liked by evangelicals.

That year my role shifted. For 12 years, I had been my son’s father, provider, protector.

Now…

I would be his first bully.

I write that with a heart filled with shame and eyes flooded with tears.

I knew those words would need to come.

I wrote them 5 minutes ago, and I’m still weeping.

I hope no parent ever makes the same mistakes I made.

Had he been anyone else’s child, I would have met them with empathy, compassion, and conversation. My exposure to the two men in my Intercultural Communications course years ago gave me great sympathy for the LGBT+ community, as had my friend Greg. But this was my son. I knew what awaited him in my evangelical world. And for every wrong reason one can imagine, I became his first bully.

Why?

Because clearly, gays weren’t well-liked, especially by evangelicals.

In all honestly, fear motivated me. I feared my overall evangelical community in relationship to my son. I knew how they spoke of the LGBT+ community. I knew the jokes, jabs, assumptions, mischaracterizations, and unilateral disapproval. The endless stream of protests, boycotts, and petitions to stop all the agendas for people like my son. They were upset about cakes, flowers, and photography for people like Grayson. I knew he would be the oddity. You know, the kid for whom “Mix It Up at Lunch Day” was created when all the evangelical kids were encouraged to stay home so as not to inadvertently affirm people like my son. I knew people would whisper, “The Boswell kid has got to be gay.” I knew they would look at him with pity, piety, or worse. They would judge his speech, posture, apparel, gait, character, and very identity. He may very well be a complex person with all sorts of layers, but he would be reduced to the pejorative “homosexual,” with an emphasis on homo.

Also, I was an evangelical pastor. I could lose my job. I’m not just saying that. Pastors have lost their positions over having gay kids, so it’s real. Our family would need to move. We had just gotten settled after a rough four years. We had just started a new church in the last year. Having an openly gay son would risk everything.

And what of our future relationship? Evangelical churches excommunicate practicing LGBT+ people. It happened to my friend Greg. People were told to have nothing to do with Greg except call him to repentance, to not so much as even have a meal with him. Would Grayson be excommunicated? Would I need to honor the words of 1 Corinthians 5-6 and never have any relationship with him ever again if he were to go down this road? What about his sisters? Honor prayed for this little brother and has adored him from day one. Emma and Grayson are only 20 months apart and thick as thieves. Would they be forced to decide between a relationship with God or Grayson?

And Ellen…

My sweet wife. She cried with sheer joy when she found out she was having a son. The pregnancy was hard. The months that followed Grayson’s birth were even more challenging due to a health issue induced by the pregnancy. She fought like hell for the first year of his life. And invested passionately every year following. Staying home as a mom. Opting to homeschool all three of the kids as their teacher. Reading countless books on Christian parenting and education. Doing everything “right” to ensure her kids turned out to be godly adults. Making every day an intentional deposit for a tight-knit family.

Ellen and Grayson are particularly close. Two peas from the same pod. What would it mean for them? For us all?

The fears piled on quickly.

And so the attempt to course correct (i.e., bullying) began.

Don’t stand like that!

Don’t sit like that!

Don’t walk like that!

Don’t speak like that!

Why are you going to wear that?

Why do you like stuff like that?

I was counseled to “Dude him up.” So I bought him a motorcycle. Built R.C. cars with him. Drug him out on hikes with a machete. Taught him to shoot guns. Made him watch “Braveheart” to see how real Scottish men act. You know, I focused on a monochromatic vision of masculinity. One in which, quite honestly, I’m not even entirely comfortable with but felt I needed to embrace to fit within my evangelical world. We did have some fun in those times, but my goal wasn’t as much fun as fixing. In hindsight, I see what this was. I’ve always been a massive opponent of Reparative/Conversion Therapy. I think it’s pretty destructive stuff. I’m grateful many states and countries have made the practice illegal. But I was engaged in a twisted version without even realizing it.

Throughout this time, he tried to talk to me about what was happening in his inner world. And I would hear him, but I wasn’t listening to him. I would push back. Challenge his perspectives. Redefine his words, his feelings, his point of view. We would banter about the nomenclature of “same-sex attraction” versus “gay.” He would maintain he was the latter, and I would retort by saying he may be – at most – dealing with the former. It was a battle of identity. How stupid I was. At the very time in life when kids are at their most insecure and vulnerable, I visited upon my son the sins of my father.

Growing up, I didn’t have the best relationship with my father. I was made to feel like I was always some disappointment. I swore I would never do that to my kid.

Until I did.

At 15, everything came to a head. Through a series of events, I discovered our son had a friendship with another young man that was more than mere friendship. The conversation escalated quickly. Grayson wanted to help me understand. I refused. He tried to stand his ground. I had intimidation on my side. I brought every verbal threat an evangelical pastor parent could muster. I could lose my job, we would lose our home, the family would be wrecked, we may not be able to maintain a relationship with you, and you may face an eternity in hell; you get the gist. In effect, I said, “You are going to destroy our entire lives if you do this.” Pretty heavy and devastating stuff to throw down on a kid trying to figure himself out. And it worked. I shoved my son back into the closet he had been attempting to come out of since he was 12. In reality, I only established a new equilibrium, a homegrown version of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” He maintained all the right words while seeking to send every, “but hey, I’m still gay” signal he could. He planned to say the right stuff until he graduated. Then he could come out without that added burden of putting his family at risk. He assumed, understandably, that it would mean no further relationship with the family who meant so much to him, but to be true to who he was would require loss and rejection.

Grayson didn’t make it to graduation before coming out once and for all. A few months into his senior year, another series of events caused Grayson to pretty much fall right out of the closet. Sitting on our front porch, he sobbed as he told me, “I just don’t believe like you believe. I just don’t. I can’t do it anymore.” That day I just held my son and cried with him. Shortly after, my wife pulled up. She held him and wept. The 5-year quest to stop the inevitable was finally at its end. Now we would find out if all our fears would be realized.

That afternoon I called our church leadership and broke the news that my son was going to live an openly gay lifestyle.

That evening our leaders and some additional close friends came to our house. We talked, cried, and prayed together. We discussed that my job may need to come to a close with this revelation. That is one of the issues our leaders needed to work through. We also decided that I would share about our son being gay at church that Sunday. Kind of crazy right? How many families have to go through such stuff so publicly? But it’s a pastor’s life in a small town. News travels fast, and I knew where there is no story, one will be created. We also discussed the need to make Grayson feel loved and welcomed at church. Ideas were tossed around about having everyone in our church write him a card of encouragement. I also asked our then youth pastor to please take an added interest in Grayson, something I had been asking for regularly but never really materialized up to this point. As the night ended, everyone hugged my wife and me. But, as my son later noted, everyone came over to comfort you, but that night only one person stopped to check on me. He doesn’t blame or fault anyone for that, but he also took note of it.

That Friday, our leaders concluded that I was not disqualified from pastoral ministry even though I had an openly gay son. On Sunday, I shared our story with the church at large. A couple of families left the church, citing I sounded too affirming, but the majority responded with compassion. It was a relief. Perhaps all my fears, all those decades of conditioning, would be disproven. Which would only highlight how awful I had been with all the needless mistreatments my son endured.

When it came to Ellen and me, we felt incredibly loved by people. Most could identify with the perils of parenthood and thus extend to us nothing but grace. But, the story with Grayson was a bit different. The idea of having everyone send him a card of encouragement never materialized, except for a couple of families who took personal and heart-felt imitative. And my hopes of our youth pastor making a proactive investment played out in an opposite manner. Instead, an entire youth group night was dedicated to all the rumors people had heard about Grayson. Our youth pastor approached me the next day to let me know about all the other things I may not be aware of that kids were openly sharing the night before at youth group. That conversation was the only time I can ever recall fully “losing my shit” regarding a fellow staff person. I was fighting for the soul of my son, and the environment I needed to step up the most was sabotaging all efforts. At my son’s work, his interactions with people from church were a mixed bag. Some would come in and double down on friendliness. He loved that. Others would come in and display a subtle aloofness where there had once been warmth. Some kids in the youth group were particularly an issue since every gossipy speculation shared on that fateful Wednesday night was codified as fact since there was never follow-up to clear the air, confront hearsay, or correct statements made.

Overall, I think some people weren’t sure what to do with him, and he sensed it. We sensed it too. And that is true with most LGBT people and the evangelical landscape. At best, pity feels far more like the emotion in play than love. In fact, I still catch hints of the pity at times when people ask how my kids are doing. When asking about my daughters, the octave is usually higher and spirited, “How are Honor and Emma?” When asking the same question about Grayson, the tone drops into that slightly burdened “bless your heart” range. Now, please understand I don’t share any of this in hurt or blame or to shame, but as a tool to learn from and grow in applying the deeply needed feature of uncomfortable grace.

It’s funny; I commonly hear evangelical people say how coming out as LGBT+ is so popular today because you are instantly hailed as a courageous hero without really doing much of anything. I can’t speak for all LGBT+ people, but I can guarantee that my son has never been heralded as any hero. I agree it took grit for him to stay the course of his journey, but precisely because he knew he might suffer significant loss and villainization. And that villain persona persists. We live in the liberal land of Seattle, and still, my son faces insults and ridicule for being gay. The first time he was openly called a “fa__ot” was walking through, of all places, a Target in Redmond, WA. Also, on a walk around Green Lake once with his boyfriend, a group of guys decided to harass “the queer-y fa__ots” who needed to stop holding hands in public. Grayson has shared other stories about the judgment he and some of his friends have faced, especially in the trans community. Even today, I talked with a dad who needed to get our local police department involved with escalating physical harassment toward their transgender child. It’s a lot of pressure when you know a large portion of the country doesn’t like you simply for who you love or the gender you sense. For every group vocalizing support for the LGBT+ community, there is a sea of counter-voices to let them know they are oddities who threaten Western civilization. That’s a lot of psychological weight, especially for a young and anxious soul.

Which brings me back to June.

Where clearly, still, gays aren’t well-liked by evangelicals.

June is Pride Month for the LGBT+ community—that time of year when the gays and evangelicals go to social media war over the rainbow. Oddly, the coalition of anti-Pride is comprised of a hybrid of backgrounds, all unified under the tent of anti-Woke politics. I find this odd only in that most evangelicals see those other faith traditions as theologically hell bound. Yet, cultural foes sometimes require strange alliances in the face of societal slide. It should be the start of a joke, “Why did the Jewish political pundit, the White Nationalist, and the Evangelical set aside their beliefs and walk into a bar? To discuss how to shut down the drag bar across the street before they’re tempted to read ‘Green Eggs and Ham’ to kids at the library.” This year’s Rainbow Wars did not disappoint, which is what was so disappointing.

Before Pride month began, there was all sorts of clamor over Bud Lite doing a marketing campaign with a transgender social media influencer. Next, there was the perennially vilified Target and its Pride apparel line. Apparently, Jesus doesn’t want LGBT+ people drinking cheap pilsner or wearing colorful clothes from non-Christian companies. Next came attacks on Chick-fil-A for hiring a head of inclusion and equity. Immediately following this were calls to cancel the television show “The Chosen”(a show all about the life of Jesus) when a Pride flag was spotted behind the scenes on the gear of a cameraman. People were gleefully posting infographics about how much the worth of Target and Anheuser-Busch had fallen in the face of boycotts. Kid Rock took to his submachine gun to wipe out a stack of Bud-Lites in protest, as though that doesn’t send a violent signal toward trans people. Others vented about how sick and tired they were of all the Pride flag stuff being jammed down their throats at every turn. Evangelicals reminded everyone of the real meaning of the rainbow and to take the colors back for Christ. Even “The Ark Encounter” in Kentucky went to social media with the Noahic replica awash in the hues of the rainbow to reclaim the colors. And as the month closed, the LGBT+ community was handed another setback as the Supreme Court sided with a Christian web developer in Colorado who did not want to provide wedding services to same-sex couples. It’s odd, but as best as I can tell, the LGBT+ community is the only group businesses can legally discriminate against regarding certain goods and services in the marketplace. I can easily see the day when a White Christian Nationalist refuses goods or services to a mixed-race couple because it violates their religious convictions regarding the mark of Cain in Genesis 4. Even atheists business may join the religious conviction model by refusing goods and services to those who disagree with the moral code of the Flying Spaghetti Monster. Based on the court’s reasoning, I’m not sure this wouldn’t be a protected position for anyone presenting a religious conviction. Then add to this all the hyperbolic speak around transgender athletes, state laws, school board meetings, and book bans, and the inevitable walk away for a person in the LGBT+ community is pretty apparent – forget whether evangelicals love you or not, they certainly don’t like you at all.

And thus… why would they ever want to listen to us?

We can’t keep dropping anti-LGBT+ cluster bombs in the culture war and then say, “But let me tell you about Jesus who loved you so much he came and died for you.” Which of us would want to lean into, learn from, and do life with a group that collectively sounds like they have little to no regard for you? I learned this lesson the hard way. I have spent years making up for it. And still, regularly, I hear the tone-deafness of my overall evangelical world on the subject. It’s all very religious but looks so little like Christ. Now, I know some will reply, “Matt, don’t forget, love the sinner hate the sin!” Great! Let’s work with that. Let’s make sure the LGBT+ community feels unmistakably loved because many think we only see them as sin.

Which brings me back to June for the last time, Pride Month, and that 6-striped rainbow flag. Many may not realize it, but the colors of the Pride flag have meaning.

Red: Life

Orange: Healing

Yellow: Sunlight

Green: Nature

Blue: Harmony/Serenity

Purple: Spirit

Neither I nor my faith convictions are at odds with those six themes. Thus, as the parent of a gay child, I confess I am grateful for the work of the Pride movement. I know that is not the evangelical thing to say, but if Christians had historically faced this issue more like Christ, I might not feel the need to admit it. My faith tradition does not have a great track record of understanding, compassion, or civic tolerance toward the LGBT+ community. We love the founding fathers and their assertion that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed, by their Creator, with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” But regarding the equality between heterosexuals and homosexuals, it’s more like Huxley, “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.” If it wasn’t for this movement, I’m not sure who would have sought to ensure the LGBT+ community would have civil rights, equal protection under the law, the right to serve their country openly, and general acceptance in everyday society. The Pride flag, to me, is not synonymous with sexual activity but symbolizes a marginalized community’s hard-fought efforts to be treated with equality, dignity, and civility. And thus, the Pride flag has a meaning far different for me; it represents a community that cared about equality for people like my son when the culture at large and the evangelicalism, in particular, would never have done so. In fact, I have found that the evangelical groups and ministries who are courageously seeking to build a bridge, bring healing, and repent for the sins of callousness and unkindness toward the LGBT+ population are doing so mainly because the Pride movement exposed our offenses of indifference and injustice. Consequently, I’m grateful for those in the LGBT+ community who went before so that people like my son would feel cared about while simultaneously confronting our tendency toward a Christ-absent Christianity regarding LGBT+ people.

So why do I write all this?

I have three asks.

And one confession.

First, I write this for every parent who comes across that moment when they discover their child may be asking LGBT+ questions. Our story stands as a cautionary tale. Whatever you do and whichever resources you seek, don’t become your child’s bully. Walk with them. Pray for them. Show the absolute best of Jesus to them. Be compelling through kindness. And ready… be prepared to learn a lot along the way. Also, feel free to reach out to me. I often find that only those who live it fully understand it.

Second, I hope we evangelicals work harder at what it means to obey Jesus’s golden rule of Matthew 7:12, “Whatever you wish that others would do to you, do also to them, for this is the Law and the Prophets.” Ask almost any LGBT+ person, and they will surely tell you how unloved they feel by those who claim the love of God… especially in June. Now, I’m not asking evangelicals to become Pride-affirming, flag-waving allies, but simply Christlike neighbors who do good to and speak kindly of their LGBT+ family and acquaintances; in person, in private, in public, and online. As a pastor friend recently said, “Wouldn’t it be great if evangelicals stopped playing the public square equivalent of ‘smear the queer’ and instead just stopped to listen to and befriend the queer?” His words rang with the echoes of Jesus when a woman was drug into the town center to be condemned by religion and instead was met by the fierce love of God. And that reminds me of what Melinda Selmys wrote in her work Sexual Authenticity, “[Sexual minorities] are not a problem for experts and theologians to solve… They are, first and foremost, the face of Christ, marginalized, bullied, misunderstood, spit upon and rejected, and absolutely beloved of God.”

Third, I invite my evangelical friends to graciously stand up for people in the LGBT+ community when they see them being bullied, mocked, mischaracterized, or treated as the butt of a joke or meme. Too often, I see online jabs and jokes directly or indirectly targeting this population. And in talking with people in the LGBT+ community, many have religious traumas related to mistreatment. We are called to be a population of peacemaking. Incarnating a counter-cultural Christ who used selflessness and grace to draw and heal wounded souls. In this, I’m not advocating we start “calling out” the bullies as bullies ourselves, but instead, we exercise a touch of humanity and privately “call in” to offer encouraging options for dealing with cultural differences in a more kindness-based way.

Finally, I write this as penance. Jesus said, “Woe to those who make these little ones stumble.” I believe that to have been my offense with my son, and for that, I must accept my fate. Like the Pharisees before me, I placed upon Grayson “burdens too heavy to bear.” I should have approached those early years like these last few. Fear drove the former; now, love and faith drive the latter. My 23-year-old son no longer claims a Christian faith, but he has shown me a Jesus-like compassion I wish I would have shown 12-year-old him.

Yesterday I sent this article to Grayson. Shortly after, he called me. He was crying and wanted me to know it was ok. That he understood why we did what we did. And that he hurt with us as his parents. He told me how much he loves me and is proud that I’m his dad. Go figure; he was looking out for me. I broke down. I’m weeping again just recounting the moment, as one slain by the power of undeserved grace.

And Grayson… we are proud of you.

I love you, “wingman.”

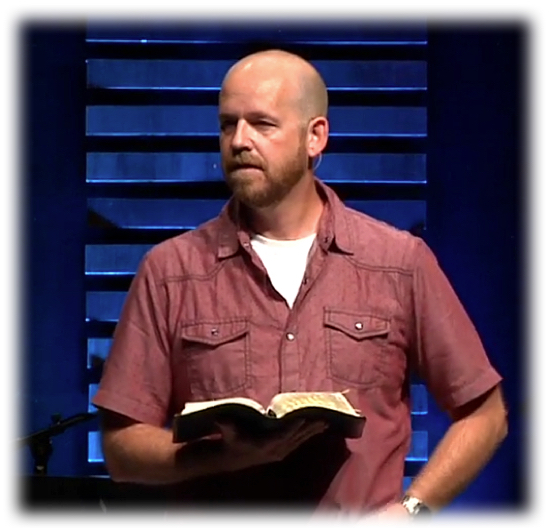

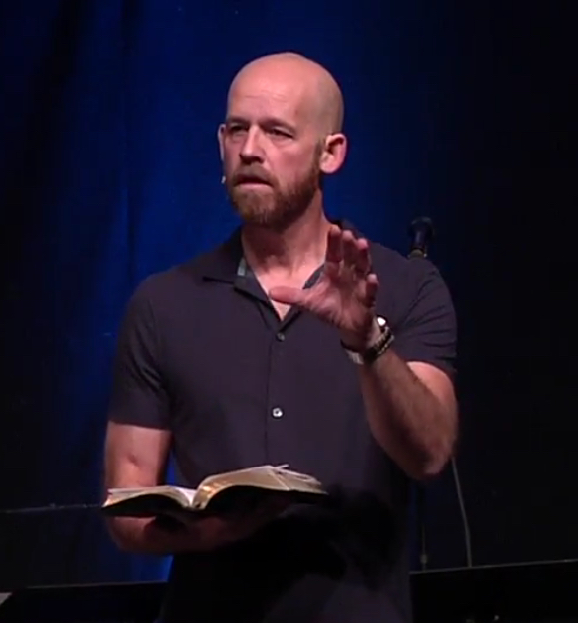

We have saved the best for last. In this recent installment of

We have saved the best for last. In this recent installment of  Three months ago our 17-year-old son shared with us that he no longer held to our Christian faith and that he was in a relationship with a young man. However, our journey with our son and his sexuality began far earlier than a fall day back in October. In this episode of

Three months ago our 17-year-old son shared with us that he no longer held to our Christian faith and that he was in a relationship with a young man. However, our journey with our son and his sexuality began far earlier than a fall day back in October. In this episode of